Ukivuk or King Island is one of Alaska’s endangered historic places. A ghost village, residents lived on the bitter edge of the Bering Sea and migrated to Nome.

Ukivuk or King Island is one of Alaska’s endangered historic places. A ghost village, residents lived on the bitter edge of the Bering Sea and migrated to Nome.

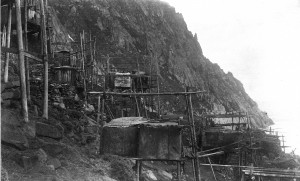

Abandoned for nearly four decades, Ukivok is one of Alaska’s ghost villages hovering precariously on a rocky cliff facing the Bering Sea on what is known as King Island. Remains of village buildings perched on poles stand eerily on the unforgiving terrain and wait for the elements to scour them from the rocks back into the sea. Ukivok (64˚55’56.09″ N 168˚01’30.15″ W) is located some forty miles from Cape Douglas on the Seward Peninsula and due south of Wales, the westernmost settlement on the mainland of North America.

King Island was listed by the National Trust for Historical Preservation as one of its eleven most endangered historic places in 2005 due to deterioration caused by natural forces. Original buildings on the island were mostly constructed of wood with walrus skin roofs. The King Island Native Corporation is greatly interested in repatriating the island seasonally and rehabilitate significant structures in the village. The important effort is seen as a key factor needed to preserve the rich Ugiuvangmiut Eskimo culture.

Inupiat Eskimos known as the Aseuluk or Ugiuvangmiut lived in the harsh environment of the Bering Sea, using Ukivok as their winter base for subsistence hunting, fishing, and gathering activities. In the summer they engaged in the same pursuits on the mainland near present day Nome, Alaska. The people more widely known as King Islanders developed a reputation for producing elaborate ivory carvings as a market for their handiwork developed with the founding of Nome.

In his journey to the North Pacific searching for the Northwest Passage, English Captain James Cook charted Ukivok and named it King Island after one of his Lieutenants, James King in August of 1778. Russian interests in Alaska closely followed Captain Cook’s activities and the first European, Ivan Kobelev landed on the island in June of 1791.

Naturalist John Muir traveled to King Island on the Revenue Cutter Corwin in 1881 and said of the island on July 12th, “Their town, of all that I have seen, is the most remarkably situated, on the face of a steep slope, almost a cliff, and presents a very strange appearance. Some fifty stone huts, scarcely visible at a short distance, like those of the Arizona cliff-dwellers, rise like heaps of stones among heaps of stones. These are the winter huts, and are entered by tunnels. The summer huts, large square boxes on stilts, are of skin, [stretched over] large poles of driftwood. There is no way of landing save amid a mass of great wave-beaten boulders. In stormy times the King Islanders’ excellent canoes have to be pitched off into the sea when a wave is about to recede. Two are tied together for safety in rough weather. These pairs live in any sea. A few gray-headed old pairs came off with some odds and ends to trade.”

In a report prepared on 20 June 1937 by Lieutenant Commander R.C. Sarratt titled Sociological Study of King Island, Sarratt reported that the village at King Island supported some 190 residents residing in 45 homes and that there was a heated school equipped with electric and water utilities.

Up until 1938, the Coast Guard Cutter Northland served the agency in the Bering Sea. The Bering Sea Patrol every conceivable mission found “under the midnight sun” that included hauling mail, transporting island villagers, gathering naval intelligence, carrying teachers, conducted coastal surveys, and generally supporting the northern population. The Northland transported King Islanders to Nome in the summers. After World War II, there was a decline in travel to King Island each September. The Bureau of Indian Affairs closed the village school in 1959 and by 1960 the U.S. Census reported an official population of only 49 residents. No one continued to live on the island after about 1970, with most King Islanders becoming full-time residents of Nome.

Copyright © 2013 by Alan Sorum